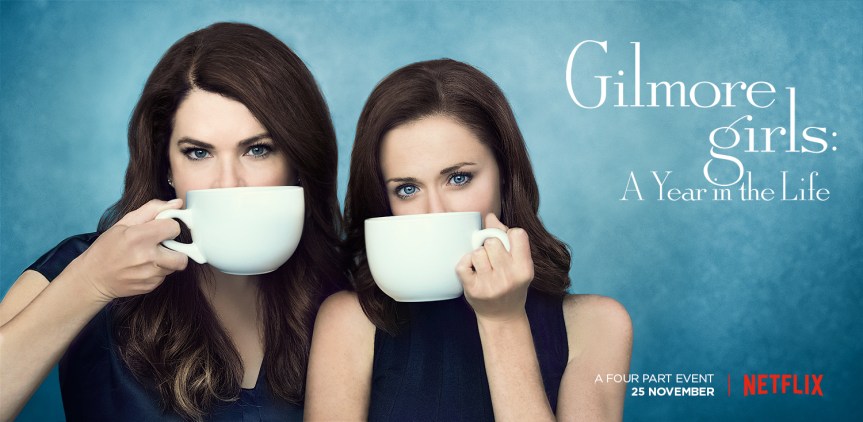

Having avidly rewatched Seasons 1-7 of Gilmore Girls in anticipation of the revival episodes, we sat down and binge watched all four of the new episodes (with plenty of tea and biscuits on hand, of course). Despite the time constraints of a much shorter series, Gilmore Girls: A Year In The Life managed to hit a lot of the right notes and walked a fine line between catching the viewer up and moving the story forward nine years. ‘Winter’ got us back into the Gilmore Girls rhythm very quickly and by the middle of the first episode, it felt like we had never left Lorelai and Rory’s world. We thought that we would share a few of our thoughts on a character-by-character basis. Needless to say, there are spoilers for anyone who has not watched all four episodes yet.

Lorelai.

Where else to start but with Lorelai (Lauren Graham)… Overall, A Year in the Life resolves Lorelai’s storyline well. Without feeling untrue to her character, we see her arc quite naturally over the four episodes towards reconciliation with Emily and openness with Luke. The Wild scenes where Lorelai leaves Stars Hollow on a voyage of self-discovery showcase Lauren Graham’s versatility and emotional depth as an actress whilst also demonstrating Lorelai’s growth as a character. In one of the most poignant scenes of the whole revival (perhaps the scene of the revival), Lorelai’s emotional phone call to her mother provides much needed catharsis as they grieve and remember Richard. The trip in turn gives Lorelai a clearer perspective on her relationship with Luke and in a lovely counterpoint to the beginning of the series, Lorelai ends happily settled down whilst Emily is the character striking out on her own.

Rory.

Rory’s (Alexis Bledel) character has perhaps the most problematic arc of the three Gilmore girls. A Year in the Life perhaps struggles in this respect with being ten years after the end of the original series. Much of Rory’s angst feels far more suited to a 20-something Rory than a 30-something Rory (indeed those famous final four words take on a very different perspective in this context, but more on that later…) Rory’s character also seems to suffer the greatest rupture between where we left her at the end of Season 7 and where her story picks up again. Rory’s relationship with Logan is most symptomatic of this. It is never explained how they transitioned from his “all or nothing” ultimatum at the end of Season 7 to a “What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas” agreement in A Year in the Life (although this is perhaps explicable in light of the return of the Sherman-Palladinos). This development does not fit naturally with how either character left us. It feels unnatural for Rory to be happy being the “Other Woman” given her previous experiences with Dean and Lindsay while Logan’s reconciliation with his family and willingness to acquiesce to marrying Odette is also unexplained.

Emily.

A Year in the Life is perhaps at its strongest when it comes to resituating Emily (Kelly Bishop) as a character in light of the death of her husband Richard (Edward Herrmann). We see her progress through all the phases of grief (including the unimaginable sight of Emily Gilmore in jeans!) Her storyline also offers a valuable chance for Lorelai and Emily to grow closer. The therapy scenes in particular offer an insight into just how complex their relationship is after so many years of miscommunication. Underneath that tension, A Year in the Life offers a sustained look at how the relationship has evolved since the end of Season 7. By the end of ‘Fall’, mother and daughter have reached a better understanding and seem set on a much better path for the future. In arranging to see each other, Lorelai and Emily have progressed to a point where this agreement is mutual rather than forced.

Emily’s character also achieves a satisfying sense of direction and self-worth beyond the DAR and her position as the matriarch of the family. In many respects, this newfound independence brings plot points to fruition that were planted during Emily’s separation from Richard in Season 5. One of the most notable examples of this is the show’s use of her history degree at the whaling museum in Nantucket.

Honourable character mentions.

Kirk and Michel make happy (and entertaining returns) but the return of the fabulous/terrifying Paris Geller (Liza Weil) is one of the most welcome and successful subplots of A Year in the Life. Paris continues to be a force of nature and fluctuates between acerbity and deep-seated vulnerability. The scenes in her return to Chilton display this perfectly when she veers wildly from terrifying school children and karate kicking bathroom doors in stilettos one moment to fragility and insecurity the next. We only wish she could have appeared in more episodes!

A few gripes.

As wonderful as it is to have Amy Sherman-Palladino and Daniel Palladino back in the Gilmore Girls driving seat, the revival suffers in some respects from having two different writers and from the episode distribution that they were given. ‘Spring’ and ‘Summer’ (DP) are hugely different in narrative style from ‘Winter’ and ‘Fall’ (ASP) and many storylines get lost between them or end up being resolved preternaturally quickly. An example that particularly grated was the storyline in ‘Winter’ regarding Luke and Lorelai considering having children. It did not feel resolved by the end of ‘Winter’ and then was never referenced again.

A Year in the Life also suffered from the natural difficulties of only having a four-episode run and the respective availabilities of returning actors and actresses. Sookie’s (Melissa McCarthy) absence was never more keenly felt than when she failed to appear at Lorelai’s wedding (despite making her only appearance of the revival, alongside dozens of wedding cakes, earlier in the same episode). The short episode run also seemed to lead to expansions and contractions of time and geography that make no logical sense. Rory jumps between London and Stars Hollow seemingly instantaneously (we wonder if the Huntzbergers have indeed invented teleportation in addition to owning all the newspapers on the planet). In a similar vein, Emily is shown in Nantucket the night before Lorelai’s Stars Hollow wedding and would have to travel at lightning speed to attend her daughter’s wedding the following day. This inconsistent sense of time also affects the transitions between episodes for the viewer. It is unclear whether each episode continues directly on from the preceding one or whether weeks or even months have passed in between.

Where A Year in the Life does do well is connecting the show’s longer past with its present through audio and visual flashbacks. One of the most emotional scenes of the revival combines scenes of Friday dinners’ past to great effect as Rory sits down to write her family’s story.

The final words.

The final four words have suffered somewhat from being reified by fans in the intervening period between the end of Season 7 and the revival. Whilst somewhat frustrating upon initial viewing, on reflection there is a pleasing symmetry in how Rory’s storyline is concluded as she mirrors the Lorelai that we met at the beginning of the original series. Many storylines come full circle from the original series in A Year in the Life and set the scene for characters to begin new phases in their lives. Ending on such a note of possibility and uncertainty leaves us feeling that we have indeed seen a year in the life of the Gilmore girls and that their world will continue to change even without us there to witness it.